Inside the Mayflower II Replica ~ 2016, Plymouth, Massachusetts

The Surrender of the Speedwell ~ Incompetence or Intent?

It’s July 1620 in Leyden, the Netherlands. The financially strapped group of Separatist Puritans finally (“at length,” writes William Bradford) bought and fitted a small ship ~ the Speedwell ~ with a plan for it to remain with them in their New World colony for fishing and “other affairs.” The larger, 180-ton ship hired in London, about three times the Speedwell‘s 60 tons, would transport the greater part of the group and return with its crew to its London base. Master Reynolds and his crew of the Speedwell were hired to remain for a year in America to aid the colonists with sailing the ship.

So, why is there no Speedwell in the Plymouth Plantation story? What happens to the Speedwell and its crew? How does this plan go awry? And what are the consequences?

After a day of “solemn humiliation” in study and prayer, the devout and determined Leyden group gathered to board the Speedwell in Delftshaven, seen off by those who would remain behind. Such expressions of true love and care were exchanged that the Dutch spectators were moved to tears. The ship and passengers set sail about July 22, and it is at this point in his story that William Bradford refers to a passage in Hebrews 11:13-16 and pens the words that would later inspire what became the famous and popular name for our American forefathers:

So they left that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting place near twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims…

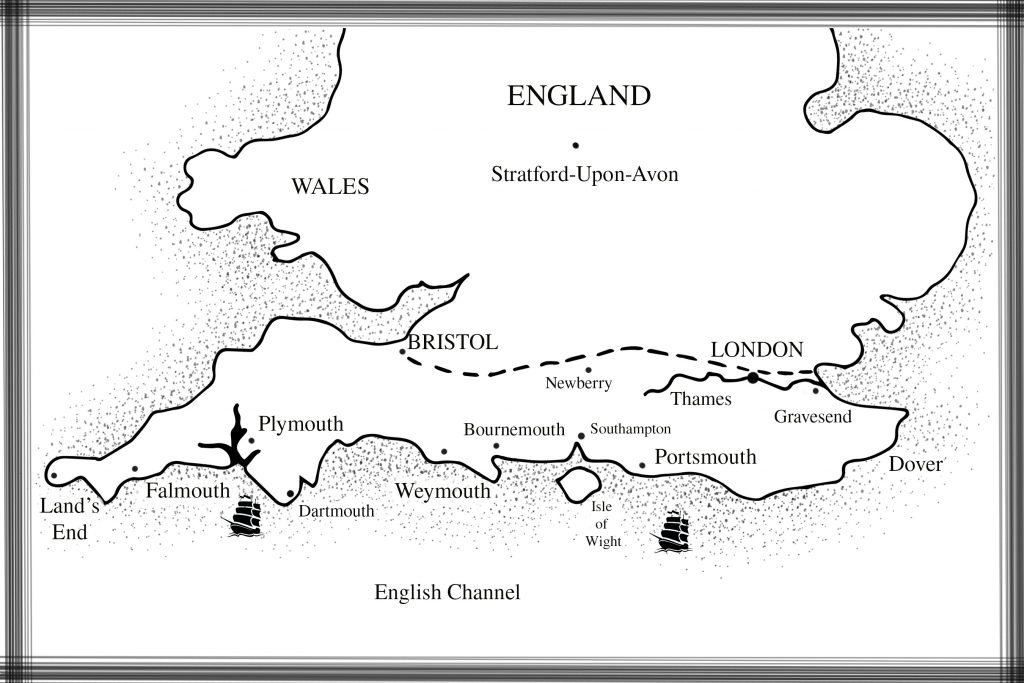

The rendezvous was in Southampton, where the church’s business representatives and the group of some 80 “strangers” awaited them. There they wasted time and good weather in an argument with the “merchants and Adventurers” (the investors) represented by Mr. Weston over the final conditions of the agreement to divide the colony’s profits and assets in 7 years, particularly the future homes and homesteads built by the colonists, which they refused to include in the “assets.” In turn, Weston refused to cover the Pilgrims’ outstanding debt of 100 pounds, so the group sold between 3,360 and 4,720 pounds of their store of butter. The wrangling and delay were not good for the confidence of either the passengers or the crews.

The rendezvous was in Southampton, where the church’s business representatives and the group of some 80 “strangers” awaited them. There they wasted time and good weather in an argument with the “merchants and Adventurers” (the investors) represented by Mr. Weston over the final conditions of the agreement to divide the colony’s profits and assets in 7 years, particularly the future homes and homesteads built by the colonists, which they refused to include in the “assets.” In turn, Weston refused to cover the Pilgrims’ outstanding debt of 100 pounds, so the group sold between 3,360 and 4,720 pounds of their store of butter. The wrangling and delay were not good for the confidence of either the passengers or the crews.

Finally, August 5, the Mayflower and the Speedwell left port. However, they had not gone far when Master Reynolds discovered the Speedwell was leaking, so they put into Dartmouth. Not only did repairs cost them precious money, time, and good wind, but they did not fix the problem. Some 100 leagues (about 300 miles) past Lands End, the still leaking Speedwell forced both ships to return, this time to Plymouth, a true naval town. Finding “no special leak,” the local experts declared that, due to “general weakness,” the Speedwell was not up to the voyage.

This was quite a blow for our Pilgrims, but, thankfully for American history and many future Americans, they resolved to continue. Those deemed the weakest and those with many young children agreed to remain in England. Bradford compares the winnowing of the group to the biblical story of Gideon’s army, “as if the Lord by this work of His providence thought these few too many for the great work He had to do.” (SEM, OPP, pg. 53)

Bradford later learned that the Speedwell had been “over-masted and too much pressed with sails” which had caused her, according to Samuel Eliot Morison, to open her seams and spew her oakum. She was sold and “put into her old trim,” and went on to perform profitably for her new owners. Bradford believed that Master Reynolds and his crew “plotted this stratagem to free themselves, as afterwards was known and by some of them confessed.” (SEM pg 54)

However, Bradford saw God’s caring hand in that one of those who stayed behind, Robert Cushman, proved to be “a special instrument for their good” over the next few years. Meanwhile, Cushman lamented in an August 17 letter to Edward Southworth that…

Friend, if ever we make a plantation, God works a miracle, especially considering how scant we shall be of victuals, and most of all ununited amongst ourselves and devoid of good tutors and regiment…

But,… down one ship, fewer in people, lower in food, losing more good weather, unresolved with the investors, the brave and believing Pilgrims stayed their course, for the sake of religious freedom and the future of a new and special country.

This post draws from both Samuel Eliot Morison’s (1952) and Caleb Johnson’s (2006) editions of William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation and Thomas Fleming’s One Small Candle (2017).