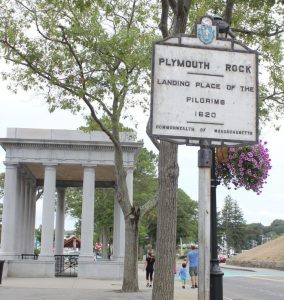

Plymouth’s Famous Rock (author’s photo)

Physical & Spiritual Rocks of Faith & Bravery

Above, you see a famous rock (boulder) that resides for viewing within an enclosure on the beach of Plymouth, Massachusetts. At some point, the date 1620 was carved into it. Look closely and you will see where the rock had broken into two pieces and was repaired. In 1741, some 121 years after the celebrated arrival of the Pilgrims, Elder John Faunce of Plymouth identified this boulder as “the place where the forefathers landed.” Faunce was 95, so was born (using only the available math) in 1646 (or thereabouts), the year before William Bradford ceased his Of Plimouth Plantation record. As a reliable source, Faunce was at least reasonably close to the original group, the “first comers.”

The memorial built around the famous rock which lies in full view on the beach beneath the structure. Plymouth harbor is to the left, town on the hill to the right (author’s photo)

Bradford writes that certain Pilgrim men who had been exploring the coast of Cape Cod in the ship’s shallop (small boat) found much needed rest and shelter on what is now known as Clarks Island, where they dried out and “gave God thanks for His mercies in their manifold deliverances.” They spent three nights, partly “to keep the (Sunday) Sabbath.” The next morning, they sounded (measured the depth of) Plymouth harbor. So, on Monday, December 11/21, 1620, whether or not they actually alighted on this boulder at low tide, they “marched into the land and found divers cornfields and little running brooks, a place (as they supposed) fit for situation.” This was their destination, they agreed, as the weather and “their present necessity” demanded a decision. They returned to the Mayflower, which lay at anchor in the harbor of present-day Provincetown, Five days later, the famous ship anchored in Plymouth harbor. We will examine the rest of the story come December 2020. [If you are wondering about the “December 11/21,” we will also have a session on the “double calendar.”]

So, the boulder, named Plymouth Rock, became the official symbol and marker of the arrival of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. It can also be seen as a symbol of the Spiritual Rock upon Whom they built their lives, their settlement, and the foundation of a country. Their Spiritual Rock was the source of their bravery, their “dauntless courage” in the face of calamity. Remember from Part I that Morison calls them “our spiritual ancestors.” If you don’t understand those basics, you won’t understand the Pilgrims.

That “Weasel Word ‘Puritan'”

Remember that the label “puritan” was neither given nor accepted as a “nice” reference. As William Bradford explains in Chapter I Of Plymouth Plantation, “at length they began to persecute all the zealous professors in the land,” and, “to cast contempt the more upon the sincere servants of God, they opprobriously and most injuriously gave unto and imposed upon them that name of Puritans.”

We see that Pilgrim Governor William Bradford had some choice words for the name “Puritan.” He makes it clear to those he assumed would read his history (and now to the whole world) that the Pilgrims professed a faith they believed to be Biblical ~ theologically “pure” and simple, back to basics, back to the teachings and practices of the first churches. They called themselves merely “people of God.”

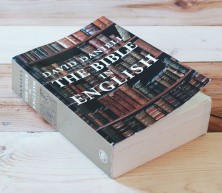

In his magnificent tome, The Bible in English (2003), Dr. David Daniell writes, “I have tried to avoid using the weasel word ‘puritan.'” (pg. xvii)

In his magnificent tome, The Bible in English (2003), Dr. David Daniell writes, “I have tried to avoid using the weasel word ‘puritan.'” (pg. xvii)

Dr. Daniell (1929 ~ 2016) was a professor of English at University College, London, and a scholar of Shakespeare and William Tyndale, particularly Tyndale’s New Testament translation. He founded the Tyndale Society in 1995 and was known for teaching, “No Tyndale, no Shakespeare.” (see his 2005 paper at Tyndale.org) The name “puritan,” explains Daniell,…

…was adopted in the 1570s by Roman Catholic writers as a vaguely insulting term for their reforming enemies, and gained prominence in the literary controversies of the 1580s and after. It was first used by ‘Puritans’ about themselves in 1605. It has since then carried the most awkward freight…, views of their emotional rigidity being drawn from (American) high-school reading of The Scarlet Letter (1850). In Britain their distinction is more usually theological. (xvii) The strength of the persistent stereotype of Puritan New Englanders as sour, repressed and joyless ‘is due in no small part to the influence of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Scarlet Letter), whose fictional works have cast a powerful spell over many generations of readers. The Puritans who haunt the pages of his novels and short stories (two centuries later) are blinkered, judgmental, repressive, and tormented. (Notes, pg. 795)

I remember my high school reading of Hawthorne’s provocative tale that heroizes his “stumblers” and deliciously trashes his 1640s Massachusetts Bay (Boston) Puritan characters. Probably the majority of American students learn relatively little about the Pilgrims ~ perhaps something about the Mayflower, the “First Thanksgiving,” Hawthorne’s highly praised “hit piece,” and the word “puritanical,” and that about sums up their knowledge of the people portrayed in funny hats who are called “the Pilgrims,” who were actually only somewhat distantly associated with those who later came to Massachusetts Bay and who represented various factions within the theological grouping labeled “Puritan.” The Salem Witch Trials of what would become the Boston area took place long after the original Pilgrims, in the early 1690s, after many more Congregational Englanders (and some commerce-focused Englanders) had come to New England. The witch trials and the involvement of Hawthorne’s uncle, magistrate John Hathorne, were a major motivation of Hawthorne’s tortured interest. [See Britannica.com for a short history of Europe’s witch hunts dating back to the 1300s, as well as a good summary of the story of 1690s Salem.]

Professor Daniel cites both Puritan and scholarly sources to show that the Pilgrims, and most Puritans, were indeed the opposite of portrayals such as Hawthorne’s. For his own sensational reasons, Nathaniel Hawthorne and others gave the Puritans (and thus the Pilgrims) a totally bum rap. Our Pilgrim Fathers (and Mothers) were brave, determined, and dedicated individuals who were neither “puritanical” nor “prudish.” They were life affirming, says Daniell, as also affirm extant love letters of Puritan couples. The specific group we call Pilgrims were passionate about their faith and passionate about all the joys of life and a loving marriage. If widowed, they sought to marry again. The union was a gift from God. The Pilgrims worked hard, risked all, endured disease, discomfort, hunger, and fear, gave continual thanks, celebrated when they could, and had lots of kids. They brewed their own beer and enjoyed a good glass of Spain’s Madeira wine when they had some handy.

In 2016, Puritan scholar Dr. Francis Bremer, who “has worked on 16 books about Puritanism,” came to Boston to debunk the myths of Puritans’ strict and prudish reputation. Madeline Bilis reports the event in her October 18, 2016 article in Boston Magazine:

Bremer explains that the Puritans got a bad rap at a time when American society was reacting negatively toward Victorian morality in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Puritans were supposedly responsible for the roots of the temperance movement, prudish attitudes toward sexuality, and a generally conservative societal outlook. The Puritan stereotype was created because Americans were “looking for people to blame for everything that they didn’t like,” he explains, thus deeming them responsible for the stuffy attitudes of the early 1900s.

Roots of the temperance movement? They brewed their own beer! And drank wine.

So, the pre-Civil War Hawthorne led the way, and, in the later 1800s, Victorian-era Americans followed. The Pilgrims were spinning in their graves! If you don’t understand that, you won’t understand the Pilgrims.

Brave Choices Despite Expected Consequences

We’ve delved deeper into who the Pilgrims were and what motivated them. Let’s delve deeper into their brave choices. We saw in Part I of this post that these village farming families were persecuted in England to the point that they made the drastic choice to move their families to a foreign country with a different language, lifestyle, and livelihood. That was a hard choice, though others of their beliefs had already done so. How do we know that? Bradford says so. [All quotes below from Chapter II of OPP.]

Being thus constrained to leave their native soil and country, their lands and livings, and all their friends and familiar acquaintance, it was much;…where they must learn a new language and get their livings they knew not how, [in a country] subject to the miseries of war [the Dutch had been fighting the Spanish], it was by many thought an adventure almost desperate; a case intolerable and a misery worse than death.

Holland was a land of tradesmen and traders, by land and sea. The Pilgrims were “used to a plain country life and the innocent trade of husbandry (farming).” Yet, “this was not all,” writes Bradford. They were blocked from leaving. He explains that…

…the ports and havens were shut against them, so as they were fain to seek secret means of conveyance, and to bribe and fee the mariners, and give extraordinary rates for their passages. And yet were they often times betrayed, many of them; and both they and their goods intercepted and surprised,…

Bradford recalls a couple of examples, one involving a ship captain hired for “large expenses” who, after loading, betrayed them to the “searchers and other officers,”…

…who took them, and put them into open boats, and there rifled and ransacked them, searching to their shirts for money, yea even the women further than became modesty; and then carried them back into the town and made them a spectacle and wonder to the multitude which came flocking…

They were released and sent home after a “month’s imprisonment,” all but seven. Bradford describes another attempt “by some of these and others” the next spring. The women and children went by boat to meet the men where a Dutch ship captain was to board them all. While the women were delayed, a boatload of the men were taken to the ship, but the captain spied armed English officers and fled. The Dutch ship “endured a fearful storm at sea,” being driven close to Norway, “the mariners themselves often despairing of life.”

And if modesty would suffer me, I might declare with what fervent prayers they cried unto the Lord in this great distress…the water ran into their mouths and ears and the mariners cried out, “We sink, we sink!” they cried…”Yet Lord Thou canst save!…Upon which the ship did not only recover, but shortly after the violence of the storm began to abate, and the Lord filled their afflicted minds with such comforts as everyone cannot understand…

A “peace that passes understanding” according to the Apostle Paul in Philippians 4:7 would most probably be Bradford’s reference.

And they arrived. Meanwhile, the rest, left behind and “crying for fear and quaking with cold,” were arrested and “conveyed from one constable to another,” until the English grew tired of it all and, they having no homes to return to, let them go, glad to be rid of them on any terms. But Bradford adds an important note:

Yet I may not omit the fruit that came hereby, for by these so public troubles in so many eminent places their cause became famous…their godly carriage and Christian behavior…left a deep impression in the minds of many.

Some few shrunk at all that happened, “yet many more came on with fresh courage and greatly animated others.” They all “gat over at length.”

A New World

They kept their faith, endured sore trials, and “came into a new world,” writes Bradford in Chapter III. And so, “it was not long before they saw the grim and grisly face of poverty coming upon them like an armed man.” Bradford indicates that it was not easy for these English village farmers to adapt to a different economy, but adapt they did. After “about a year,” for various reasons, this group moved from Amsterdam to Leyden, and “at length they came to raise a competent and comfortable living, but with hard and continual labour.” Bradford became a weaver, while Pilgrim leaders William Brewster and Edward Winslow ran a printing press. The Pilgrims were so true to their word, diligent, and honest, that they soon earned great respect among the Dutch.

As this commemorative year progresses, we will look at the reasons they chose to leave Holland after 12 years residence there and the hard choice of yet another move, this time to a brave new world of extreme challenges.