The Pilgrims Were Headed for Virginia?

We saw in a previous post titled “The Year of the Mayflower” (Feb 2020) that the Pilgrim Fathers had a patent to settle their own, independent colony within the greater Virginia (which stretched from modern-day South Carolina to mid-Maine), with intent to settle somewhere along the Hudson River, and that Plymouth was already named on John Smith’s map (a copy of which the Pilgrims had purchased), but that the New Plymouth was not on the itinerary. So, how did they end up on the coast of Massachusetts? Even more important, why was this congregation of Separatists wanting to risk a challenging, if not deadly, move to the New World? For them, it was something akin to relocating to Mars. And what were Separatists?

In the 1530s, King Henry VIII became the original English “Separatist” in that, for his own political and personal reasons, he separated England from the Roman Catholic Church that dominated Western Civilization, forming the Church of England (Anglicans). The intent was not to protest nor to reform, but to cut the cord from the rule of the Pope. Despite that, it is called the English Reformation which followed the Protestant Reformation of Luther in 1517 (actually 1521). When Scotland’s King James came to the English throne in 1603, he became head of the Church of England. Both the Church and the King continued to be threatened by rebellious Catholics and bothered by obstinate, Bible-reading church groups who wished to separate themselves completely (no compromise) from the government-ordained and controlled Anglican Church. Freedom and independence are not good for legally required conformity.

As William Bradford explains in Chapter 1 Of Plymouth Plantation, “at length they began to persecute all the zealous professors in the land,” and, “to cast contempt the more upon the sincere servants of God, they opprobriously and most injuriously gave unto and imposed upon them that name of Puritans.” So, Puritan was not a nice name, and it came from the English religious enforcers. King James was a zealous man in his own right.

As William Bradford explains in Chapter 1 Of Plymouth Plantation, “at length they began to persecute all the zealous professors in the land,” and, “to cast contempt the more upon the sincere servants of God, they opprobriously and most injuriously gave unto and imposed upon them that name of Puritans.” So, Puritan was not a nice name, and it came from the English religious enforcers. King James was a zealous man in his own right.

The persecuted group preferred to be called God’s People. Bradford belonged to the Scrooby congregation in Nottinghamshire, under organizer William Brewster and pastor John Robinson. Increased persecution drove the congregation to escape to the Netherlands and the open-minded Dutch folk. Though it was tough to make a living, the group lived there “for some 11 or 12 years,” when it became too obvious that the Dutch were too open minded, and the group’s children were losing both their Englishness and their “pure faith.”

The New World beckoned. Virginia’s Jamestown colony was established and viable by 1617, and Pocahontas had visited the King and Queen, but scary stories still lingered of famine and disease and torture by Indians. A few true cases made the Anglicans sound friendly by comparison. A lot of people died keeping Jamestown on the map. Money was also an issue, as well as another hard move to a strange place. However, though the “dangers were great,” writes Bradford in Chapter 4, they were “not desperate. The difficulties were many, but not invincible.” The answer was “Go.”

How About Guiana?

Guiana?! Really? Our Pilgrim Fathers could have gone to South America? How would that have shaped history? And the character of New England? Would their progeny, already exposed to Dutch culture, raise up future sugarcane planters? And possibly slave owners? What a possibility to ponder.

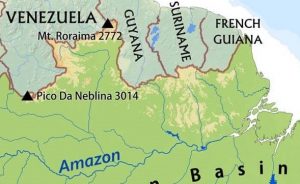

Columbus sighted what became known as Guiana, the Wild Coast in 1498. Other Spaniards arrived in 1499. The vast area between the Orinoco River (Venezuela) to the mighty Amazon (Brazil) would be divided by Europeans into Venezuela (Spaniards), Brazil (Portuguese), British Guyana, Dutch Guiana (Suriname), and French Guiana. According to Britannica online, the Dutch began with trading posts on the Essequibo River (Guyana) in 1580. In 1595, between captivities in the Tower, Sir Walter Raleigh made an expedition to the region and published, in 1596, Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana with a Relation of the Great and Golden City of Manoa (which the Spaniards call El Dorado), Etc., Performed in the Year 1595, by Sir W. Raleigh, KNT. Other voyages and publications would follow, one in 1613. The never-say-die search for the elusive El Dorado has continued to modern day, featured (in a form) in 2018 with a trip by Parker Schnabel (Gold Rush TV show) and friends to find gold in the jungle of Guyana. Today’s Guianas are tourist destinations. Such is history.

Columbus sighted what became known as Guiana, the Wild Coast in 1498. Other Spaniards arrived in 1499. The vast area between the Orinoco River (Venezuela) to the mighty Amazon (Brazil) would be divided by Europeans into Venezuela (Spaniards), Brazil (Portuguese), British Guyana, Dutch Guiana (Suriname), and French Guiana. According to Britannica online, the Dutch began with trading posts on the Essequibo River (Guyana) in 1580. In 1595, between captivities in the Tower, Sir Walter Raleigh made an expedition to the region and published, in 1596, Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana with a Relation of the Great and Golden City of Manoa (which the Spaniards call El Dorado), Etc., Performed in the Year 1595, by Sir W. Raleigh, KNT. Other voyages and publications would follow, one in 1613. The never-say-die search for the elusive El Dorado has continued to modern day, featured (in a form) in 2018 with a trip by Parker Schnabel (Gold Rush TV show) and friends to find gold in the jungle of Guyana. Today’s Guianas are tourist destinations. Such is history.

Back to the turn of the 17th Century, the Dutch established a settlement 25 kilometers up the Essequibo in 1616 (Wikipedia). So, in 1617, the Leyden (Netherlands) British Pilgrims would know about Guiana. After much prayer, Bradford records in Chapter 5, the Pilgrim group called a huddle to consider destinations. “Some (and none of the meanest) had thoughts…for Guiana.” Bradford uses “mean” here in the sense of “middle” or “average.” He is saying that leaders and those of higher status proposed investigating “fertile places in those hot climates.” Having read the tourist brochures, they promoted the idea of a country “rich, fruitful, and blessed with a perpetual spring and a flourishing greeness” where, in short, the good things of life were abundant and easy.

Who wouldn’t go for that? Easy eats and spring all year. Thankfully for American history, New England, and everyone, “cooler” heads prevailed. These people knew only northern climes. Their wardrobe was tweeds. Other things considered, writes Bradford, it might not be “so fit.” There were “grievous diseases and many noisome impediments” to weigh on the scale. And then there were the Spaniards. And the Dutch. Next on the list, Jamestown, might be worse for these “Puritans” than the home country. And Jamestown tales made “the weak to quake and tremble.” North was better.

Though the Dutch had named the Hudson River by way of Englishman Henry Hudson who sailed for them, and the Dutch were active in Manahatta, the region was claimed by England as part of Virginia, so, “some place about Hudson’s River,” Bradford writes in Chapter 9, was the answer. According to the note by Samuel Eliot Morison, the Pilgrims’ patent promised local self-government, fishing and fur-trading rights, and protection from the Dutch (far away from the Spaniards).

The early journals of Bradford and Edward Winslow, known as Mourt’s Relation (1622), indicate a “river 10 leagues to the south of the Cape,” and a 1622 letter by the visiting Secretary of Virginia, John Pory, states “their voyage was intended for Virginia.” (see SEM, OPP, page 60, note 6)

So, How Did They Get to Cape Cod and Massachusetts?

We’ll explore that question in further installments of our series, The Year of the Mayflower (listed under Categories). A note on the maps included here ~ Nerd has purchased four books of maps, allowed for free use, from FreeWorldMaps.net and will be using those in our Braving the New World book and study guide. The two maps here are borrowed from the website.