A Significant Date for Some Famous People

The year 1616 was significant not only to Pocahontas, Squanto, and Captain John Smith, but also to men who would become two of the world’s most famous writers ~ William Shakespeare and Miguel de Cervantes.

They are both said to have died on April 23rd of 1616, Shakespeare at a mere 52 and Cervantes at 68. Because of their works and their influence, English would become known as the language of Shakespeare, and Spanish would be called la lengua de Cervantes (the language of Cervantes). Declared by the Spanish to be “The Prince of Wits,” Cervantes wrote his popular Don Quixote later in his life. It would eventually be recognized as the first modern, European novel and one of fiction’s greatest works.

As for April 23rd, Shakespeare apparently did die on that date in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon (perhaps on his birthday), but Spain’s Cervantes actually died on April 22nd and was buried on April 23rd. However, there was that sticky wicket of separate calendars for over a century and a half. Spain had gone along with the Pope and adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1582. England remained on the Julian Calendar until 1750. So Shakespeare passed 11 days after Cervantes, and 10 days after his burial, though both dates say “April 23.”

Whew! Calendars ~ often a historian’s nightmare.

On the same date of April 23, 1616, Spain also recorded the death of the half-Spanish, half-Incan historian Garcilaso de la Vega (Gregorian Calendar, we assume). I remember discovering his Royal Commentaries of the Incas in the university library. I was fascinated! Since April 23rd is connected with a number of prominent writers, the United Nations declared the date “World Book and Copyright Day” in 1995.

Saint George, the Martyred Soldier

But April 23rd is connected with yet another well-known personage ~ a dragon slayer ~ St. George.

But April 23rd is connected with yet another well-known personage ~ a dragon slayer ~ St. George.

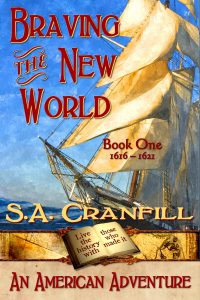

In my historical-fiction novel, Braving the New World, I take full advantage of the actual business relationship and interaction between three important individuals: ship captain and explorer Thomas Dermer, the “American” Squanto, and the famed British knight turned colonial investor, Sir Ferdinando Gorges, who was Governor of Plymouth Fort (England) in 1618. In my fictional dialogue (based on real documents and events), Gorges relates to Squanto the story of his group’s failed venture into Maine called the Popham Colony. When he mentions the building of Fort St. George, Squanto raises a question:

“Uhm-m,” grunted Squanto. “Friars in Spain spoke of saints. You talk of warrior who killed great dragon?”

“Saint George and the dragon. That is the legend,” answered Gorges, pleased that Squanto seemed to be following his narrative. “George was born of Greek noble families who were devout Christians. He became a soldier under Roman Emperor Diocletian ~ actually, an officer in the Emperor’s guard. Diocletian ordered his Roman army to worship none but Roman gods. George refused and boldly declared his Christian faith. He was terribly tortured and executed. Despite the Reformation, the Crown and the Anglican church retained George as England’s patron saint. You see his red cross on our flag.”

“Uhm-m,” Squanto grunted again. Falstaff (my mouse, hiding as usual in Squanto’s vest pocket) thought Squanto most probably did not understand Rome or the Reformation, but he had received teaching from the Catholic friars and from John Mason’s Anglican wife (in Newfoundland). He seemed to respect what he had learned about the Christian faith. He certainly respected bravery.

Thinking on the date April 23, Falstaff the mouse would probably have uttered, “My, what a date!”